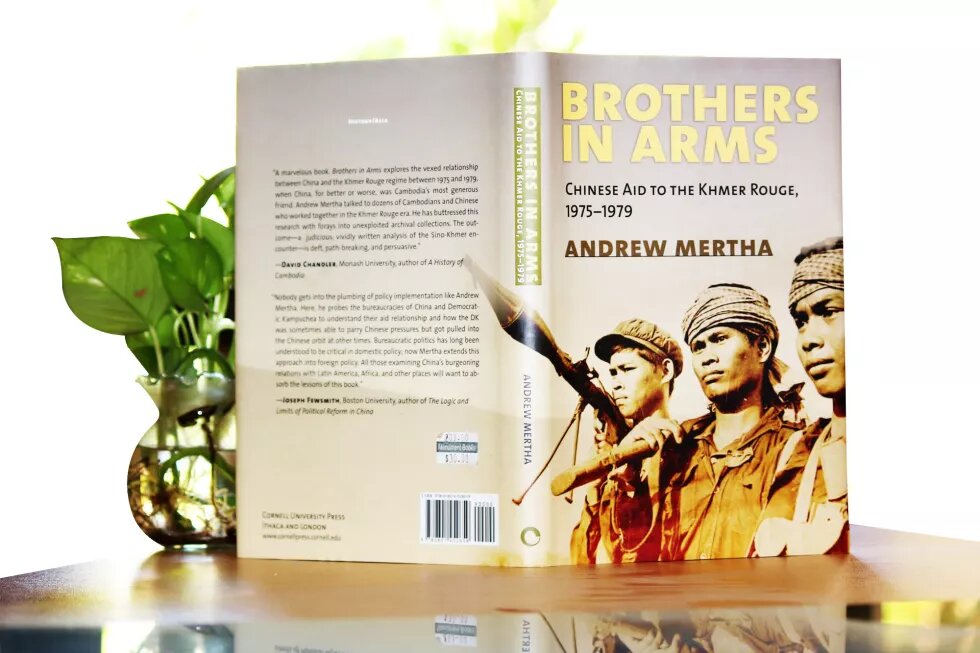

Why was China, a powerful state, incapable to influence Cambodia, a much weaker state during the years of Khmer Rouge mass atrocities? What did China get in return for its development aid? Can historical analysis reveal something about the current political environment? These are some of the questions Andrew Mertha, a professor at Cornell University, dwells into in his book Brothers in Arms: Chinese Aid to the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979.

He argues that Chinese aid bought little due to the ‘bureaucratic fragmentation in China’ (p. 9) as well as the institutions in Cambodia that were either able to resist Chinese demands or incapable to act on them. Mertha points out that the Chinese and Cambodian Leninist systems were different; therefore, it was difficult to understand one another. There were three dimensions of Chinese aid to Cambodia: military, infrastructure, and trade. China provided Democratic Kampuchea (DK) with training and materials such as weapons and communications equipment. The non-military aid was agreed to be a loan of 140 million yuan and 20 million USD. According to the research, Chinese influence on the military and infrastructure sectors was very minimal whereas trade was largely shaped by the Chinese.

The considerations on the normative aspects of the Sino-DK relations highlight their complexity. On one hand, the Chinese in the DK most likely knew that something sinister was happening around them even if they did not know the magnitude of the killings. However, Chinese leftist leaders who visited the DK admired the Communist Party of Kampuchea’s work towards socialist utopianism and did not seem to be disturbed by the oppression of the Cambodian people. Perhaps the most shocking notion that the author makes is this: even though China did not manage to change many aspects of the Khmer Rouge regime to be more beneficial for China, it had an enormous role in supporting the whole existence of the regime. On the other hand, individual Chinese people in the field brought glimpses of humanity to Cambodians who worked and lived under hard conditions. The Chinese workers took risks in order to relieve the Cambodians’ suffering by for example sharing their food with them. However, taking more pressing action by complaining about the situation would have risked being transferred back to China. More alarmingly, the Cambodians who had worked with the Chinese who had complained would have most likely been executed.

The book has many dimensions in the sense that it considers both Chinese and Cambodian politics during both the Khmer Rouge era and today. Mertha considers the way analysing history can help understand contemporary politics, especially in China. There are some similarities between the past and the present, for instance, the great amount of Chinese military aid to Cambodia. Since the start of the millennium, military aid has grown to five million dollars a year. China has also been active in other sectors, especially in infrastructure by constructing hydropower plants. Furthermore, another dimension he raises is the relationship between the domestic politics and foreign policy of China. However, when it comes to Cambodia, it is much harder to spot similarities between the eras because of the brutality of DK. Nevertheless, the author also raises a different kind of historical point: the Chinese who came to work in DK experienced, in a way, a déjà vu since they had already witnessed political purges in their home country. This example highlights the multifacetedness of Mertha’s book and therefore, its value as an exploration into the bilateral relations on different levels and eras.

Mertha, A. (2014) Brothers in Arms: Chinese Aid to the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.