Victim Participation in Cambodia’s Transitional Justice Process

Please click here to download this report

Report Brief - November 2018

This research aimed to understand victims’ perceptions of justice and reconciliation in Cambodia and the influence of their inclusion in the transitional justice process. This is of particular interest as many resources and hopes have been invested in enabling victim participation in the transitional justice process in Cambodia, both at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) as well as in broader civil society projects. Our data was drawn from a survey and in-depth interviews with victims of the Khmer Rouge who participated in various ways. Data was collected between January and June 2018. In addition to the survey and in-depth interviews illustrated in the graphs, interviews were conducted with 21 transitional justice professionals in Cambodia.

JUSTICE

The survey respondents defined justice in multifaceted ways, focusing strongly on “knowing who is right and wrong,” “establishing the truth” and notions of fairness, honesty, transparency and impartiality. In-depth interviews revealed punitive or retributive conceptions of justice, as well as a social justice conception that frames justice in terms of socio-economic support. Buddhist beliefs did not undermine these conceptions but complemented them, allowing interviewees to make sense of the legal and institutional aspects of criminal justice at the ECCC through their own Buddhist perspectives.

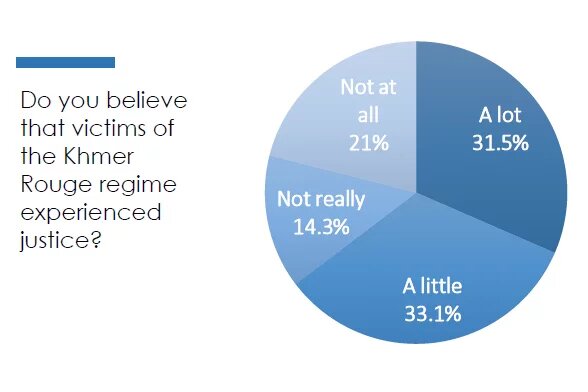

Confirming previous studies, the survey showed very positive assessments of whether justice had been achieved for the victims of the Khmer Rouge regime. In-depth interviewees were more critical, mostly often mentioning the lack of reparations as a stark limitation in the quest for justice. Other issues raised included political interference, a lack of acknowledgment of their responsibility by the accused and the length of the trials. The ECCC’s contribution to justice was rated positively, but NGOS were also perceived as important actors.

RECONCILIATION

When asked what the notion of “reconciliation” means to them, almost half of our survey respondents referred to ideas of unity and living together, while a further fifth defined reconciliation as the absence of violence and conflict; in the interviews, not holding grudges and forgiveness featured prominently, tying into Buddhist conceptions. As such, our respondents expressed a “positive” interpretation of reconciliation as unity and harmony rather than reconciliation merely as the absence of “negative” conflict and violence. Reconciliation was primarily perceived as an outcome that is achieved mostly by external intervention, rather than as a process between actors. The ECCC and NGO projects’ contributions to reconciliation were valued positively, but the government, as well as religion, were also perceived as key to reconciliation provision, emphasising the contribution of Buddhist conceptions to support conventional transitional justice measures.

The depth of achieved reconciliation in Cambodia was mostly shallow within local communities arguably as a result of a post-Khmer Rouge politics of shifting all culpability from low-level former Khmer Rouge to the Khmer Rouge leaders and the organisation abstractly.

ECCC

Our data revealed low levels of factual knowledge regarding the ECCC and Cases 001 and 002. There was, however, a statistically significant impact of the degree of participation at the ECCC on individuals’ knowledge: the more an individual had participated in the process, the higher their knowledge tended to be. In addition, men had a higher degree of knowledge than women, although this did not hold true for civil parties, a possible reflection of gendered access to general education in the patriarchal Cambodian society.

Perceptions of the ECCC were very positive regarding independence and trust. In the survey Cambodian staff at the ECCC gained the most trust, while in the in-depth interviews victims more openly displayed mistrust of the national staff and higher trust for the internationals. The generally positive perceptions also manifested themselves in a broad desire for the ECCC’s work to continue and 80.2% of survey respondents wanted Cases 003 and 004 to be tried.

PARTICIPATION

Both civil parties’ and complainants’ main motivations for participating in the ECCC was to obtain justice, have their suffering acknowledged, tell their story and know the truth. During the application process almost one third of civil parties and one sixth of complainants surveyed were afraid, mainly of revenge or pressure from the accused or their families.

A vast majority of the civil parties were satisfied with their participation. Meeting other civil parties, participating in civil party forums and visiting the ECCC constituted their most important experiences. However, many observed a strong decrease in opportunities for participation and information on the ECCC proceedings, that may threaten previous achievements and lead to a decrease in civil party

engagement with and interest in the ECCC.

Complainants were also largely satisfied. However, only one in five complainants surveyed had the opportunity to attend a hearing or to visit the ECCC, exemplifying one of the many differences in opportunities for participation between complainants and civil parties.

80% of civil parties who testified at the ECCC valued this as a positive experience, mostly for the possibility to tell one’s story in front of others or to confront the accused, while others emphasised more negatively the inability to tell their whole story, the fear of speaking in front of many people and sharing their story publicly before sharing it with relatives.

Some rejected civil party applicants did not know about their status and those who did shared feelings of disappointment, hopelessness and distress at having had their applications rejected, even feeling that their victimhood was being questioned by this.

Whilst more than half of individuals who were selected in our survey for having participated in an NGO project could not remember their participation; those who did remember showed high levels of satisfaction with this experience.

NON-PARTICIPATION

Non-participation at the ECCC was mostly involuntary and mainly related to an absence of necessary pre-conditions for meaningful participation in the early stages of the transitional justice process, including a lack of information on the ECCC and not being aware of possibilities for participation, being afraid, as well as individual incapacity, particularly a lack of time or the advanced age of the victims. The survey also provided evidence for voluntary nonparticipation, as respondents indicated nonparticipation as a rational choice with the costs outweighing the benefits, as not approving of the ECCC or as having no interest in the ECCC.

EMPOWERMENT

Participation helped many civil parties cope better with the loss of their loved ones, helped them feel mentally stronger and gave them more hope for the future, while at the same time also gave them selfconfidence to speak out about their story. Also, participation facilitated gains in knowledge that allowed individuals more opportunities to take proactive roles in their communities, as well as participation making civil parties more articulate in formulating their ideas and demands. Some individuals were also empowered in more contentious ways, challenging the transitional justice system itself through boycotts, demonstrations or signed petitions when it did not match their interests. However, empowerment was also limited by the way some programmes were designed that possibly led more to passive consumption than active engagement. A few participants in our research mentioned that they were chided when they were too vocal or critical. Furthermore, they perceived access to these programmes not to be equal by all victims, marginalising some people outside patronage networks.

REPARATIONS

Surprisingly, 81.4% of our respondents (including an overwhelming majority of civil parties) could not name a single reparation project and demonstrated little knowledge of what projects actually constituted reparations. While 22.2% of survey respondents believed individual financial reparations were the most appropriate reparations for victims today, 93.9% agreed that it is necessary to provide symbolic reparations, such as memorials, health services, education or infrastructure. Of particular prominence in the in-depth interviews was the idea of individual financial reparations, which can be used to perform religious ceremonies for those loved ones lost during the Khmer Rouge regime, as well as collective reparations, such as the construction of stupas or memorials, provision of social services (health care and education) or the establishment of a foundation for victims. For the future 64.7% of survey respondents hoped for

individual (financial) reparations and 61.3% mentioned the establishment of a truth commission. Other desires included more general references to peace and non-recurrence of the Khmer Rouge regime, justice and more prosecution.

For more information please see our report at http://www.uni-marburg.de/cambodiavictimhood