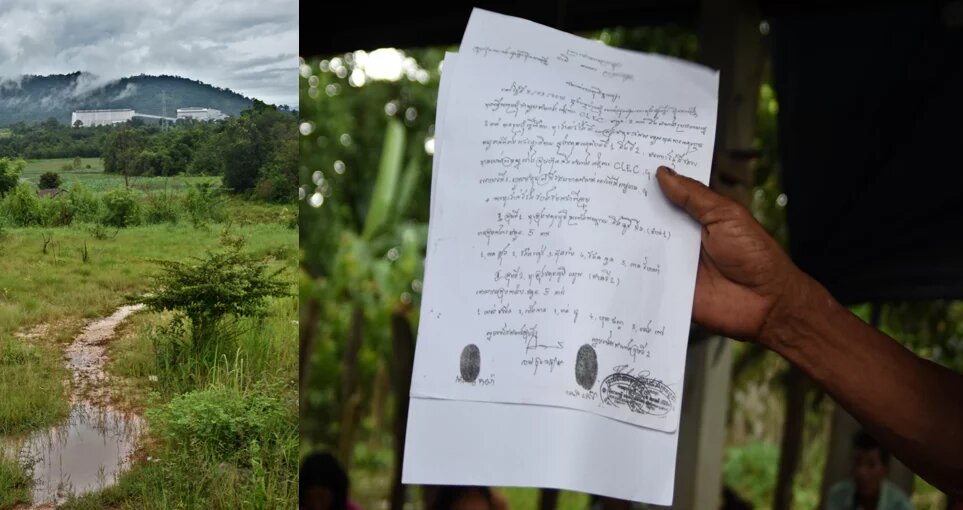

Teng Kao sits at a stilted house in Koh Kong province’s Sre Ambel district. A thunderstorm passes through the village, dousing the area in Monsoon rain. Three police officers sit just outside the meeting room, recording and monitoring the village residents — an unfortunately routine occurrence for the community.

Kao is surrounded by fellow community members listening to him recount their battle against corporations producing or sourcing sugar from Cambodia. The sugarcane companies — two of which are linked to a powerful ruling party senator — have been accused of using state resources to evict the community from their land, destroying their livelihoods and creating economic circumstances that resulted in the use of child labor at the plantation.

The greed for international investment and economic development failed to benefit the Sre Ambel community, with most citizens often left in a more vulnerable position than before the corporation arrived in their commune or village.

“Because of this situation, we lost our livelihood, our children stopped going to school, some of us had to migrate in search of jobs and many fell into debt,” Kao says.

But the Sre Ambel community’s advocacy and fight for their rights is one of the few success stories in a country riddled with land disputes. After a decades-long effort, the community agreed to a deal with UK-based Tate & Lyle for an undisclosed amount and were, separately, given small parcels of land, far smaller than what they had lost, by one of the local companies accused of human rights violations.

The out-of-court agreement was a landmark deal for the land community, which had only faced opposition from Cambodian courts and law enforcement, which consistently sided with the local companies.

The village residents were not alone in this fight. Equitable Cambodia is a Cambodian land rights non-governmental organization that works with communities to advocate for their rights, but has also successfully used international dispute resolution mechanisms to find justice for communities.

The NGO has worked extensively with land communities in Koh Kong affected by sugarcane plantations and has helped communities in Oddar Meanchey file a similar complaint in Thailand. Equitable Cambodia also advocates against predatory microfinance lending at the International Finance Corporation and achieved an ongoing investigation against major Cambodia-based microlenders.

Back at Koh Kong, Kao has been at the forefront of this legal battle, often facing the risk of violence and retribution from local authorities and the lure of bribes to turn his back on the community. The roadblocks placed against his and the community’s advocacy did not deter the community. In 2016, the community walked around 250 kilometers to Phnom Penh to advocate for their land and rights.

“Our village can be a role model for other communities. It is crucial to build good relationships, to communicate peacefully, and not to fight against local authorities,” he says.

While the community has seen small successes in their fight for their land, others in neighboring districts have not been so lucky. In 2023, around a dozen community members also affected by the same sugarcane plantation were detained and are on trial. Their fight continues.

This article is an excerpt from "Profiles of Courage." Click here for the full reading.